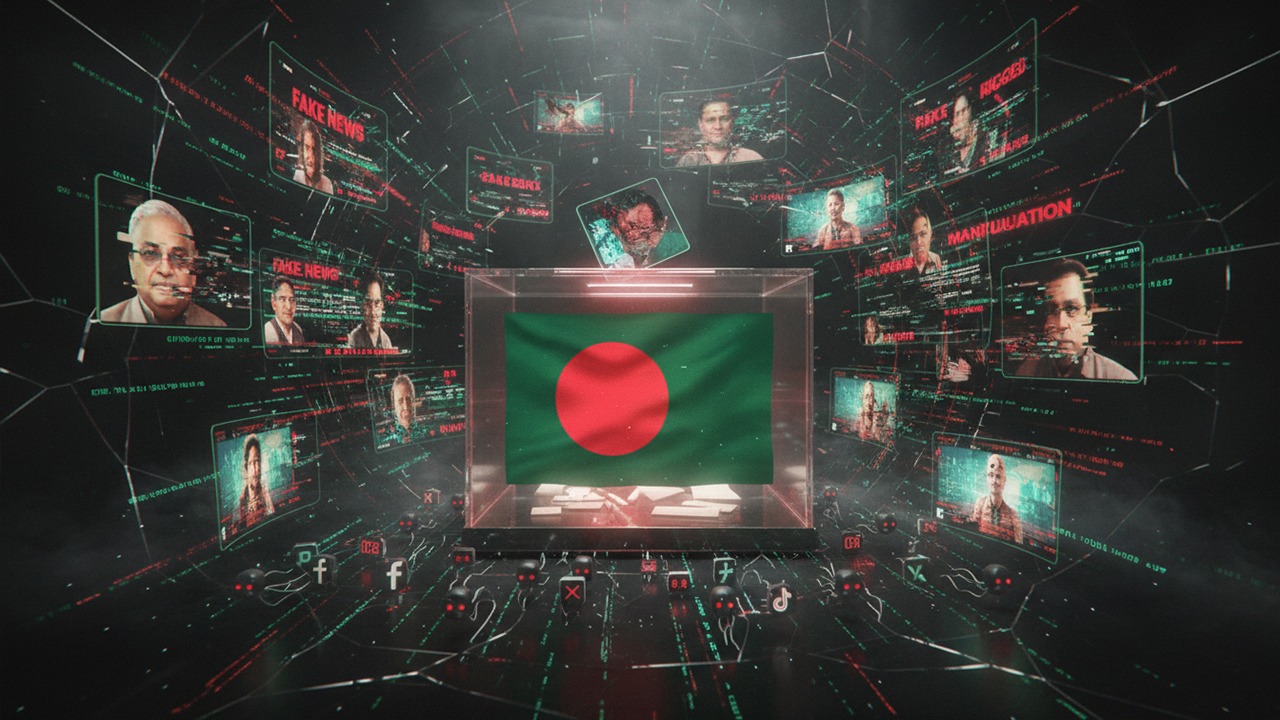

AI, Elections & The Fragility of Truth: Bangladesh at a Crossroads

As Bangladesh prepares for its national election, the country faces a problem that goes far beyond the typical issues of vote security and political violence. The integrity of information itself is under threat. For the first time in the country's political history, artificial intelligence-generated misinformation - from deepfake videos to synthetic audio and falsified news reports - has emerged as a major danger to democratic participation. This phenomenon, known as 'AI slop', indicates a significant shift in how influence, manipulation, and political persuasion work in the digital age.

The swift spread of coordinated inauthentic activity on social media platforms is at the core of this problem. In Bangladesh, networks of automated and semi-automatic accounts, known as "bot armies," are always in operation to propagate rumors, amplify false narratives, and create the appearance of public consensus. These networks frequently pose as independent expert commentary or reputable news sources, making it more challenging for regular consumers to discern between manufactured lies and reliable journalism.

Such technologies can turn false information into perceived reality in a matter of hours in a media environment where emotionally charged content spreads much more quickly than confirmed reporting.

Generational split and the 'Liar's Dividend'

Public perceptions of this issue reflect a concerning disparity between awareness and readiness. Interviews with voters from various demographics show that, while citizens realize the existence of modified information, there is a significant difference in how they perceive its influence.

Older voters frequently express skepticism. Mr. Shafik Ullah, a senior voter and business owner from Khilgaon, admitted to doubting the legitimacy of several web videos but remained convinced that such content would not influence voting behavior. This view represents generational cynicism, but it risks underestimating the long-term, subconscious impacts of digital influence.

Younger voters, on the other hand, are more acutely aware of the threat. Mr. Sish Mohammed, a university student, stated that watching a fake video of a politician may immediately influence his political judgment. He discovered that first impressions established by emotionally charged content tend to last even when factual changes are made.

This dynamic exemplifies what experts call the 'liar's dividend' - a situation in which the sheer volume of misleading material not only misleads voters but gradually erodes trust in all information, even verifiable data. The end result is not just misinformation, but a general weakening of trust in democratic debate.

Institutional capacity and structural risk

Concerns about institutional preparation are common. Ms. Tanjin Prity, a mid-level professional, expressed a frequent concern about the Election Commission's technical ability to recognize and respond to sophisticated AI-generated content at scale. While regulatory organizations are making efforts to adapt, there is growing recognition that domestic institutions alone cannot keep up with quickly changing generative technology.

These threats are exacerbated by inherent flaws in Bangladesh's digital infrastructure. Rural areas, where digital literacy is low and access to verification tools is scarce, are especially vulnerable. In these situations, video and audio content provided via private chat systems is frequently seen as authoritative. When disinformation spreads here, correcting it becomes extremely tough.

An additional, lesser-known risk affects international voters. With ballots distributed throughout the Bangladeshi diaspora, a temporary window has created for targeted disinformation attempts to influence expatriate voters before domestic voting begins. This asymmetry enables bad actors to influence external voting behavior in ways that may not be immediately apparent to election monitoring within the country.

Defending the Cognitive Domain

In response, the government has begun to build defensive mechanisms, such as 24-hour monitoring units and programs encouraging digital provenance standards, such as the Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity (C2PA). While these safeguards are progress, they are insufficient without widespread platform enforcement and public support.

Finally, technical precautions and regulatory measures are inadequate on their own. Democratic resilience in the age of artificial intelligence is mainly reliant on public knowledge. Recognizing automated behavior, scrutinizing 'leaked' recordings, and comprehending platform labeling of AI material are increasingly essential civic skills.

Bangladesh’s experience is not unique; it reflects a global challenge confronting emerging and established democracies alike. As generative AI becomes more accessible, the battle for electoral integrity will increasingly be fought in the cognitive domain. In this environment, the right to vote remains indispensable—but the ability to discern truth from fabrication will determine whether that right can be meaningfully exercised.